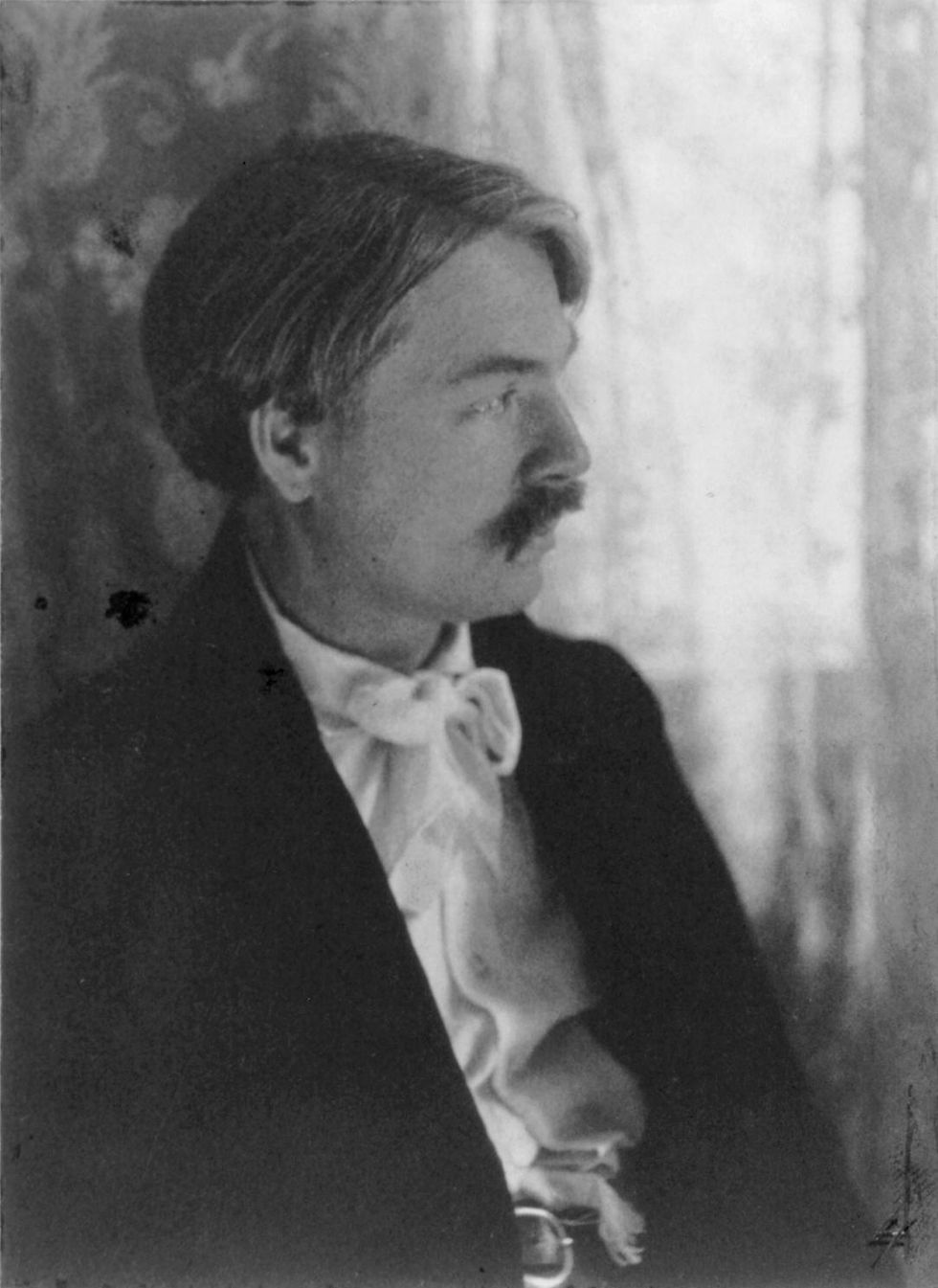

Youthful Optimistic Vitality - Edward MacDowell

- Grant Gilman

- May 26, 2020

- 3 min read

Having already covered two of the Boston Six—John Knowles Paine and Amy Beach—this week I will continue with three more: Edward MacDowell, Arthur Foote, and George Whitefield Chadwick.

Edward MacDowell once gave a lecture on “Folk-Music” wherein he illustrates his view on what constitutes American music. It is the most articulate statement I have read to date, and offers a great deal to discuss. Here is an excerpt:

A man is generally something different from the clothes he wears or the business he is occupied with; but when we do see a man identified with his clothes we think but little of him. And so it is with music. So-called Russian, Bohemian, or any other purely national music has no place in art, for its characteristics may be duplicated by anyone who takes the fancy to do so. On the other hand, the vital element of music—personality—stands alone.

...we have here in America been offered a pattern for an ‘American’ national musical costume by the Bohemian Dvorak—though what the Negro melodies have to do with Americanism in art still remains a mystery. Music that can be made by ‘recipe’ is not music, but ‘tailoring.’

...before a people can find a musical writer to echo its genius it must first possess men who truly represent it—that is to say, men who, being part of the people, love the country for itself: men who put into their music what the nation has put into its life; and in the case of America it needs above all, both on the part of the public and on the part of the writer, absolute freedom from the restraint that an almost unlimited deference to European thought and prejudice has imposed upon us. Masquerading in the so-called nationalism of Negro clothes cut in Bohemia will not help us. What we must arrive at is the youthful optimistic vitality and the undaunted tenacity of spirit that characterizes the American man. This is what I hope to see echoed in American music.

Beginning with Dvorak, he did encourage American composers to embrace Negro and Native American music as a source for the American sound, and then wrote his 9th Symphony in deference to those influences and his time in the ‘New World’. MacDowell ironically rejects ‘tailoring’ of music to impose “the trademark of nationality,” while not only favoring one history over another, but using the Native American in title and subject of his Second Suite for Orchestra (1892). Further, it is interesting to consider that MacDowell suggests that while the “personality” of music “stands alone” it is somehow disconnected from “purely national music.” Is this possible, to completely disconnect all aspects of music from one’s own influences? That is exactly the issue MacDowell claims to have struggled with his entire career. Though I do not believe he was completely successful, personally I am glad MacDowell carried over much of his European Romantic influences.

To MacDowell’s last point, this is by far his strongest, and is the best encapsulation of the distinct American music sound that was just beginning to develop. Properly, Romanticism gave music the freedom to expand, to sustain tension longer, to increase the dramatic moment (or moments). The influencing factor of America on the world’s culture is not at all insignificant, and has frequently been referred to as positive and optimistic. Regarding music, MacDowell offers a clear path of what is to come: “the youthful optimistic vitality and the undaunted tenacity of spirit that characterizes the American man.”

In the music itself, MacDowell shows every bit of what he professes. The Second Suite, beyond a tributary to the Native American culture, is full of lush melody and climactic moments. Though individual aspects of the piece can be extracted and labeled as programmatic, there is no overarching story, nor do the discernible melodies originate from the same tribes. Rather, the effect as a whole is moving and constantly engaging. Referring to the 4th movement, MacDowell would later reminisce “Of all my music the Dirge in the Indian Suite pleases me most. It affects me deeply and did when I was writing it. In it an Indian woman laments the death of her son; but to me, as I wrote it, it seemed to express a world-sorrow rather than a particularised grief.” Even to MacDowell, the programmatic reference was less important than the music itself.

MacDowell’s orchestral output is small and rarely performed. It is an unfortunate loss, though hopefully a temporary one. We deserve to benefit from the vivacity and optimism of this American music pioneer. Having mostly composed songs and likewise been a poet, I leave you with his own words, showing his faith in movement from darkness to light:

The dark hath many dear avails, The dark distils divinest dews; The dark is rich with nightingales, With dreams and with the heavenly Muse.

Comments